#5 Updates from Law, Economics and Policy

Regulation, Hart's lost essay, Monetary Policy, Passenger-data-salad from PMEAC

I wish you all a Happy New Year. Some exciting ideas were discussed in the previous week online and elsewhere; here’s a quick summary.

Law

Prof.

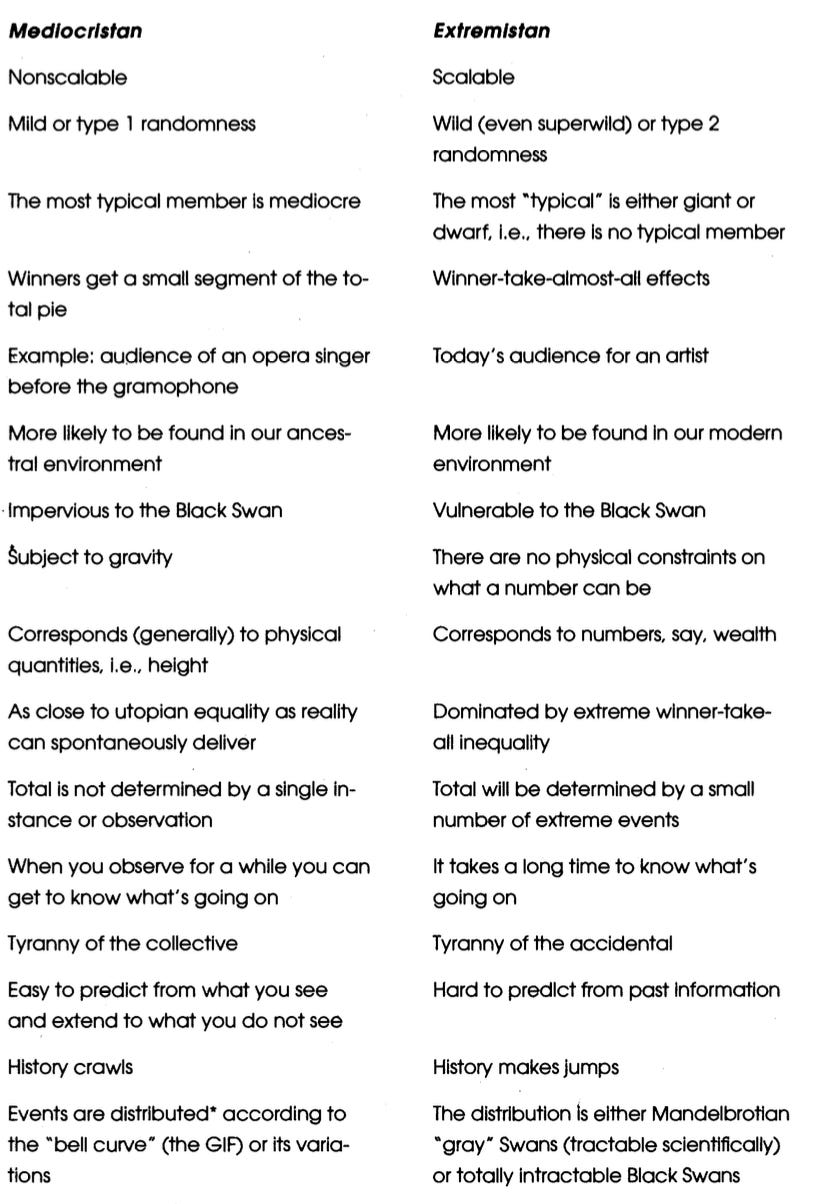

writes on Regulation in Knightian UncertaintyProf. Cass argues that in the presence of Knightian-Keynesian uncertainty where probability configurations are not understood; regulators should proceed cautiously, learn slowly, apply the maximin loss-averse rule and sleep well at night. Cass quotes Keynes's three-fold solutions—rely on history, presume existing signals have gathered the related possibilities, rely on collective wisdom— and then proceeds to reject them, again following Keynes. The principle of insufficient reason is also then summarily rejected as arbitrary. In uncertainty, the unknowns are not equi-probable and there is no reason to presume the same.

GLS Shackle happens to be my favourite exponent of uncertainty. I previously wrote about his work in the context of uncertainty here. Shackle lays bare in much careful depth the pure theory endeavour advanced by Knight. He adds the importance of distinguishing probability as a way of thinking from probability as a class feature, following Mises. But his account is criticised as nihilistic, how do we choose?

Cass is also sensitive to the argument that spending on the safety of black swan failures is politically expensive unless there is near consensus on the extent of devastation ex-ante the event happening. He suggests we can use maximin only when little is lost from following it. But, that is precisely unknown. Theoretical predictions must guide any probability modelling of particular safety behaviour, and we thus descend into an infinite regress. Cass proposes that we deploy Maximin. He says we employ subjective probabilities to produce a crude cardinal ranking of potential outcomes under uncertainty. Cardinal rankings are possible in regulatory contexts, he suggests. (I disagree, see below d. for example)

This has already been argued by Shackle in his book. (See Epistemics and Economics, Chap. 34)

He suggests we use rule-of-thumb probabilities, or on occasions even without explicitly assigning probabilities. We are guided by collective experience and practitioner expertise. We have to often cross the river by feeling the stones. What is hard for a perfectly predictable, frictionless system is worse in a social system modulated by efficiency concerns—law, economic policy for example. One question though always remains: at what point does such decision-making stop being a full rational profile/description of choices?

Confucius left us with sage advice: “When you know a thing, to hold that you know it; and when you do not know a thing, to allow that you do not know it; —this is knowledge.”

Related:

What Cass’s argument means is that sceptical empiricism is the only scientific approach to uncertainty. Platonic, romantic grandstanding and haphazardness can be damaging in the abundance of leptokurtosis. (See p. 284 of the Black Swan, Taleb N.)

Think: Is loss aversion bias an appendage of uncertain decision-making? Or is it that our loss floors have now shifted?

Conservatism is also the growing norm in uncertain-time monetary policy for example. There is also a growing conversation about conservatism in uncertain environments in economic policy-making of fragile systems. See this paper ‘easy money is no free lunch’, and Rajan R.’s book on unintended consequences of monetary policy. Also, see his lecture on the book here.

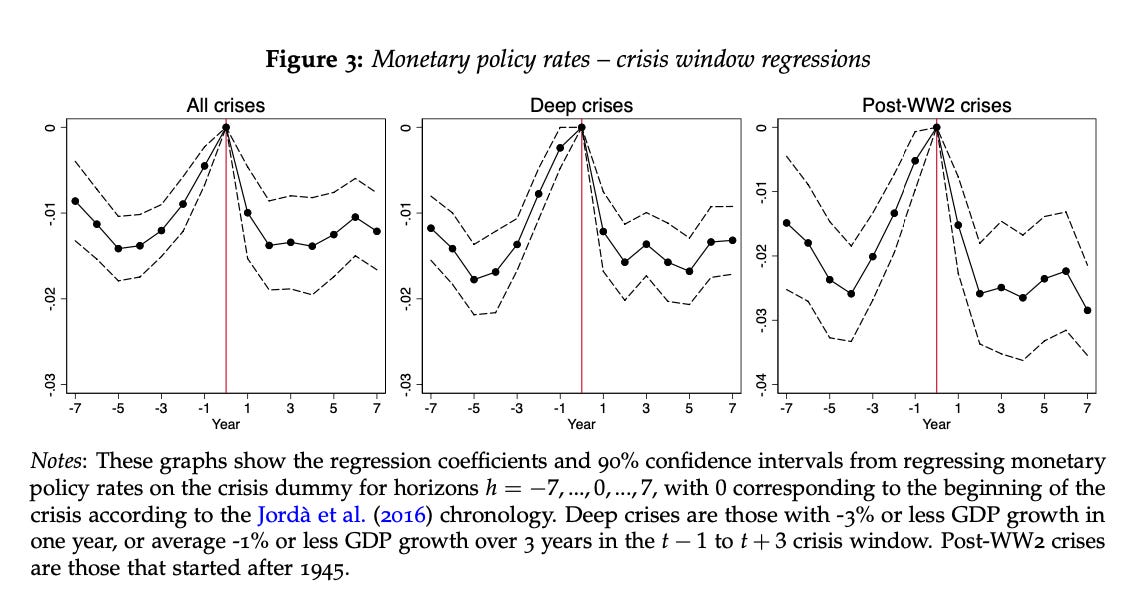

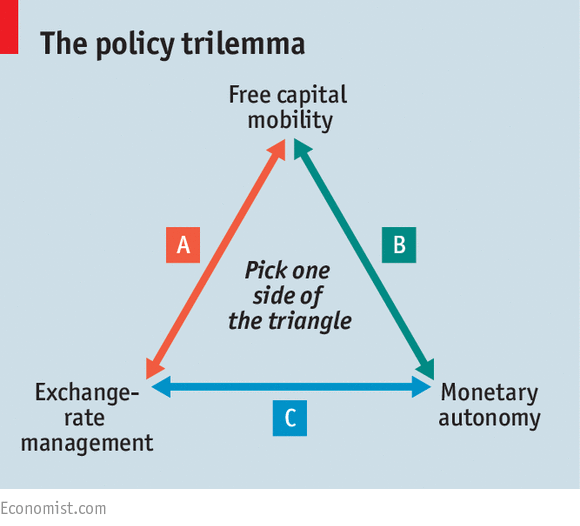

One of my favourite papers on this, which Rajan refers to, is this study of the history of monetary policy. It is a phenomenal paper, studying 87 instances of financial recessions affecting banking systems over in 17 countries over 150 years. They demonstrate an eerie pattern of banking crises which are triggered by long rate cuts followed by sharp rises—what the authors call U-shaped monetary policy. Asset prices shoot and then bust suddenly. The entire paper is worth reading, but stare at the graph long and hard. These are unintended consequences of operating in uncertainty, they also correlate with bank stock returns and profits. The authors also employ the trilemma instrument to demonstrate the conditionality of crises on long periods of cuts or low rates before the hike, leading to expectations of a particular regulatory environment and moral hazards.

Mises developed the Knightian idea in Chapter 6 of Human Action. These ideas remain central to understanding entrepreneurship, theories of firms, and technological change. But, combining a conceptually purer theory of Knightian-Mises uncertainty and theory of value, Shackle gives a powerful conceptual tool in horizon-agnostic economic analysis of varying uncertainty by declaring that reason must compromise with time. (See chapters 26-35).

If you believe the disputed Taleb thesis, the modern world is likelier to experience black swans—rare high-cost outliers—because complexity means more fat-tail leptokurtic distributions.

Hart’s lost essay was published in HLR and makes important observations relevant to law and economics.

“Of course the fact that decisions are about the scope of an existing abstract right means that the Courts do not approach their task of decision as act utilitarians and decide each case solely by reference to utility, but this only means that rights have some weight or count for something in a system where legal rules confer rights.”

- Policy, Principles and Adjudication, Hart H.L.A.

Hart demonstrates that judges deciding hard cases based on arguments of policy is neither undemocratic, nor inefficient, nor unfair. If one merely reframes arguments of policy in some policy-oriented cases as arguments that determine the “scope of rights” it doesn’t take away the soul of the purpose of the enquiry, namely that it has a utilitarian and consequentialist underpinning. This diluted version of rights that is only an anchor for decision-making would only admit that rights count for something (they are not absolute) and judges do not act as plain utilitarians. The judge’s sense of appropriateness might derive from policy and not only rights.

Questions that I am pondering upon:

(i) Are all policy arguments necessarily moral? Can a decision ever be purely utilitarian without there being an underlying norm captured as a right or by some other conceptual category? Wouldn’t such a decision be an infinite regression sans an Archimedean point? Is some version of a right based in principle a defining feature of any norm-based social organisation?(ii) At what point does employing a policy argument amount to lawmaking? Is strong discretion necessary for making policy arguments?

(iii) What is the essential distinction between policy in its reference to a moral value and a right in its reference to a moral value? Is it only to be wrapped in a vocabulary of substantive justice, like Sandel would or Dworkin would?

Warren and Brandeis on Right to Privacy and its limits, writing in 1890! Sheer foresight.

“The right of one who has remained a private individual, to prevent his public portraiture, presents the simplest case for such extension; the right to protect one's self from pen portraiture, from a discussion by the press of one's private affairs, would be a more important and far-reaching one. If casual and unimportant statements in a letter, if handiwork, however inartistic and valueless, if possessions of all sorts are protected not only against reproduction, but also against description and enumeration, how much more should the acts and sayings of a man in his social and domestic relations be guarded from ruthless publicity. If you may not reproduce a woman's face photographically without her consent, how much less should be tolerated the reproduction of her face, her form, and her actions, by graphic descriptions colored to suit a gross and depraved imagination.”

Economics

Let the rupee fall

Arvind et. al, in a series of three articles, argue that the rupee needs urgent depreciation. The artificially appreciated rupee hurts us and exposes us to unwarranted risks. Sajid has argued this before, and so has KP Krishnan.

Since 1991 we have allowed a free hand for the exchange rate with minimal interventions on three principles. 1) Allow depreciation by capital outflows that are not abrupt 2) Allow appreciation on account of import competitiveness and rise in productivity 3) Build reserves from inflows to tackle exchange rate crises; rest laissez faire. Ila’s excellent paper on India’s exchange rate regimes is highly recommended for context.

What is happening according to Subramaniam et al.?

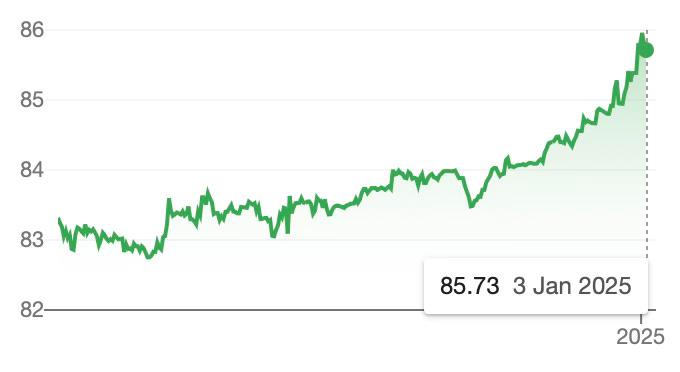

The RBI has changed its exchange rate policy regime. The exchange rate has been nearly flat for about two years and has not been allowed to depreciate (See the chart below). This has been done by exhausting reserves in the spot exchange market, non-deliverable futures market, and more direct and drastic control using regulatory powers! The latter two are unprecedented and extremely risky. The rupee has been virtually pegged to the dollar and the rupee is closely tracking the movement of the dollar.

The dollar in real terms has appreciated and most other emerging economy currencies have depreciated in response; except the rupee. This has hurt exports and cost us a ballpark, 5% of growth in two years, relative to what could have been possible. This, was while we had loaded reserves necessary to tackle capital flight.

NDF foreign market transactions have been resorted to because trying to peg the rupee by selling dollars in the domestic markets dry-up liquidity and control is difficult. The liquidity fell below the recommended 1.2% of NDTL more than once. The RBI recognised this and cut CRR by 50 bps. NDF transactions are convenient because they allow one to settle the difference in dollars in foreign markets without disturbing domestic liquidity.

An overly appreciated rupee is also susceptible to a run on the rupee leading to a drastic correction. Such a thing is modulated by the RBI's attempt to drop speculative volumes by requiring users to explain contracted exposures in onshore markets on speculation. But the RBI also tried to (which is an insane leap) regulate speculation on the offshore NDF market! Given how sharp the depreciation has been relative to other countries, the pressure on the rupee can worsen very fast, RBI is pining that the pressure eases before it is limited either by reserves or liquidity concerns. Oral instructions to banks to settle transactions in non-dollar currencies and other interventions in the currency market through regulatory power are worrying trends.

It is also difficult to understand what is the anxiety driving this stark break from the past. Taper tantrum anxieties according to me the most plausible explanation for the de facto peg. Rajan has theorised this in his book pointing to the limits of flexible rates. As the FED cuts rates, if receiver countries allow flexible appreciation, they draw even more capital and have sharper appreciation in turn. The reason for manipulation is therefore macro-prudential, often as in this case, even at the cost of real economic targets. Sharp appreciation lays the seeds for fragility. Tighter domestic policy to reign prices also leads to domestic corporate borrowing chasing cheaper dollars which has then to be directly regulated or it fuels the appreciation. A sterilised purchase itself is also contractionary in the long run, adding to the firm-borrowing. Leverage builds up substantially and when the source country raises interest rates after a sustained dip, the receiving country's bank and firm (some evidence here) balance sheets get sudden undue exposure. Equity flight forces a drastic correction. The correction in the Fx itself is damaging through various channels and forces a sharp policy rate hike. Any sustained dip by the source country makes the receiving country reasonably anxious about the dip as well as the rise that follows and it is compelled to take away the volatility of its currency. However, stabilising the currency has to be accompanied by sterilisation in the domestic liquidity market, which erodes control over liquidity and affects banks’ financial positions. (See p. 45-47 in Monetary Policy and its unintended consequences)

It appears in this case that we may be depreciating the rupee gradually, but it remains to be seen (see chart below, starting in October). Liquidity is in record deficit and was there all of December. Banks are worried as the short-term lending rates are at a four-year high and seek Forex swaps. It remains unclear whether the volatility is driven by month-end demand, closing of positions and other contingent factors or is a change of stance by the RBI. Clarification is awaited from the new guv. With tax outflows starting, more pressure on the rupee, and a neutral rate stance by the RBI, until budget spending kicks in; the RBI has to rush to its tools again. Once we have a better sense of food inflation and how the Rabi is tempering it, we might be in a position to affect a rate cut in February easing some liquidity constraints. But, the RBI also will have to square off the unprecedented open forward positions.

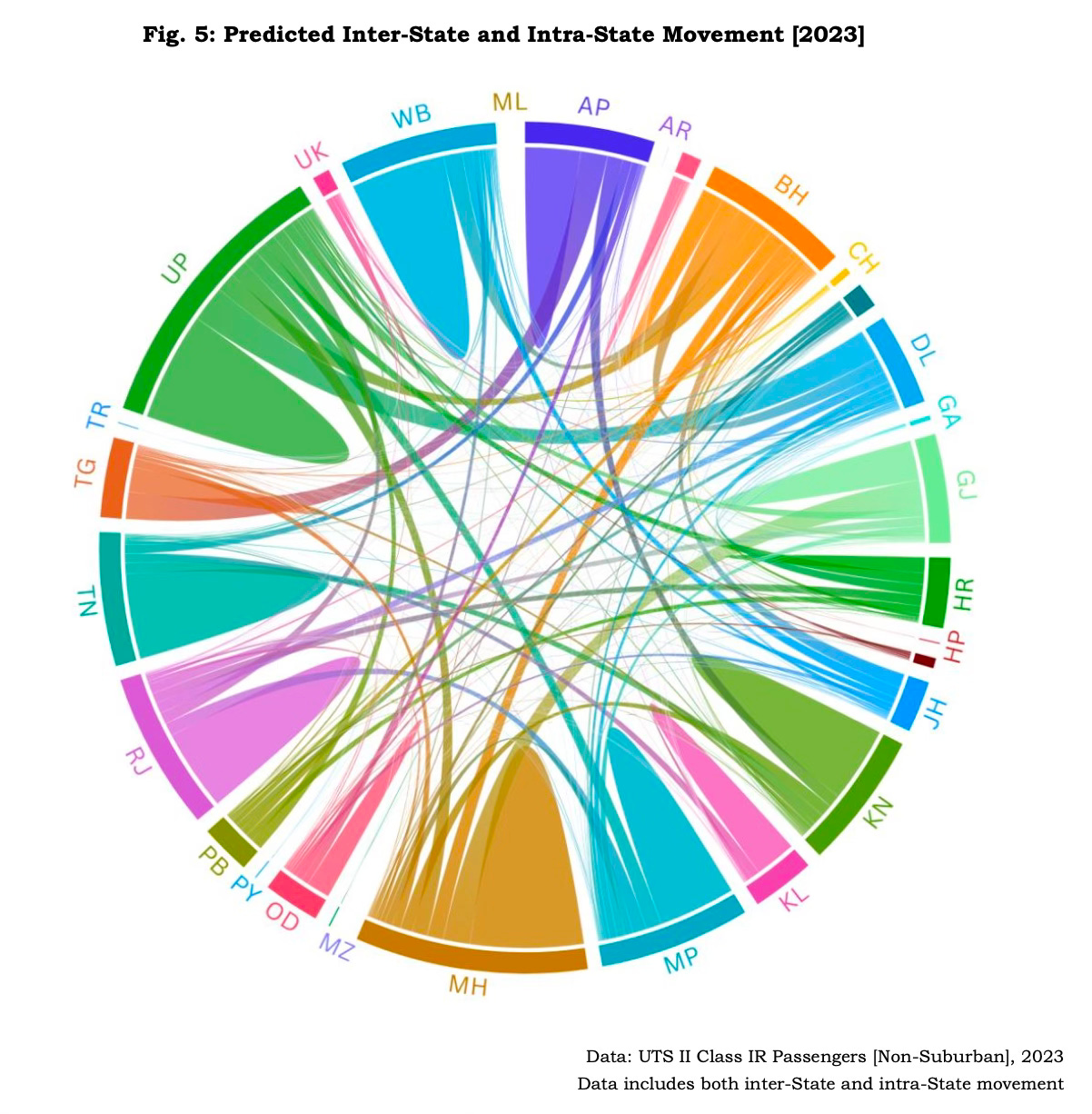

Data Salad from the PMEAC on Passenger movement, calling it migration (Link here)

Blue-collar, marriage-related and other movement trends (not migration) within India using the Unreserved ticketing data on railway passengers’ second-class travel and roaming data (which is a little more problematic) was sought to be studied in this paper.

The following problems are evident:

The paper seems to have confused transport and movement with migration and the two are indistinguishable in the paper. There is no comment on the distinction and definition of predicted migration flows as separate from passenger flows. It seems as though the paper presumes that at least a large proportion of all second-class unreserved travel is migration! That is a fatal flaw. While the caveats are identified they are not addressed. The paper lands on the finding that

75% of migration flows are within 500 kms. 40 crore migrants total, 8.5 pp decline(!?) in migration.

The paper is studying the passenger flow of 2023. It’s not hard to imagine people who migrate and stay longer than a year. Census migration studies studies migration by place of birth or usual residence. Only 8% of people had migrated in the last year in the 2011 census.

Circular migration within the year is unaccounted for.

It is hard to derive anything about migration using passenger data unless it is an identified panel of travellers, otherwise using cohort-based dyadic gravity models can lead to difficulties. Much care is warranted unless full migration histories are available. See this discussion by Rees on the empirical analysis of migration using the Ravenstein framework.

The ticketing system serves 2 crore passengers daily and has voluminous data. The data used is only for travel more than 150km as described in the railway data; The dyads are only station-station and not city-city. Further, calculating net flows to a city/district is challenging. e.g. Valsad often occurs as a popular destination but Valsad-Mumbai is one of the most frequented routes, and Valsad is only an intermediate destination.

The explained variation of 2011 Census migration data by proximate time passenger data is high. But that could only be because of the direction of migration and movement is to urban centers which are visited for other reasons. The census estimated 45 crore all-time all-cause migrants in 2011.

We cannot even loosely infer that these flows are migratory by circumstantially relying on the seasonality of flows. The peak is in May-June and November-December which are festivals, holidays, agricultural seasons, and everything else. All major economic time series blips in those months.

It would have been useful to have a split of seasonality by inward and outward travel correlated with some economic outcomes/ ranked to know if it was a gravity model at work. It would also have helped to have separate charts for intra-state and inter-state flows by distances travelled.

Nevertheless, here is a chart on passenger travel. In ten years, we haven’t added any new popular stations, states, or destinations for travel :

The year 2024 in charts from Gulzar Natarajan. We have surpassed 1.5 degrees of warming above pre-industrial temperature. Indian equity was amongst the best asset classes in the world. Key Development Challenges from the World Bank.

Let the students fail classes, remediation is essential

The centre allows detention of students in class 5 and class 8; remediation is recommended. Evidence suggests detentions do not affect learning outcomes. Does it act on teacher motivation and dropouts? But, we don’t have robust evidence yet. For now, we are riding on the logic that when we catch a fever, trashing the thermometer is not a solution. Eighteen states and two UTs have already scrapped the policy after a 2019 amendment. Expulsion is barred, and students must get remedial education.

Great read 🙌