#2 Teaching-learning Crisis in Indian Schools and the Politics of Implementation

Institutions that can't breathe freedom, can't transmit freedom. Education is freedom.

Today, I am writing one post instead of two because what I am writing about is a national emergency, and it is about a thing close to my heart.

Akshay Mangla, a professor researching development, recently wrote a blog post on the politics of schools and learning. He emphasizes that “Implementation generates its own politics” and that is the bottleneck of Indian schooling. The article merits close reading many times. It is an excellent primer on rules, discretion, culture, politics, and human flourishing if read closely. The book on which the article is based is itself valuable; a book I wish I had written (much like 1, 2). We seek to engage with this article in the later part of the blog. But, before we turn to the book or the article itself, it begs the question; why does the book matter? What is the politics in education? Why should you and I care?

Our last train to Prosperity…

A short answer is that this is our last train to prosperity; material, spiritual, or otherwise. The learning crisis has never been more colossal and urgent. Ten more years and it will be too late. It’s now or never. We are in a sinking ship. Why do I say that?

Some of us know things are bad in school education, but let us first spend time to understand just how bad! Let us focus on rural data, because that is where the data is better. For some context, 82% of our schools, 90% of government schools, and 70% of our students are in rural areas. So that is still, most of India and on most counts, urban schooling is not too different.

Learning for a toss: Adolescents in Rural India

34,745 rural adolescents across India between ages 14-18 were surveyed in 2023 after the pandemic by ASER. Let us start with that. One in four children aged 14-18 could not read a level II Hindi/ Vernacular text and most tested adolescents couldn’t do basic arithmetic problems. Pause for a while on the responses to some questions posed to these adolescents and think carefully:

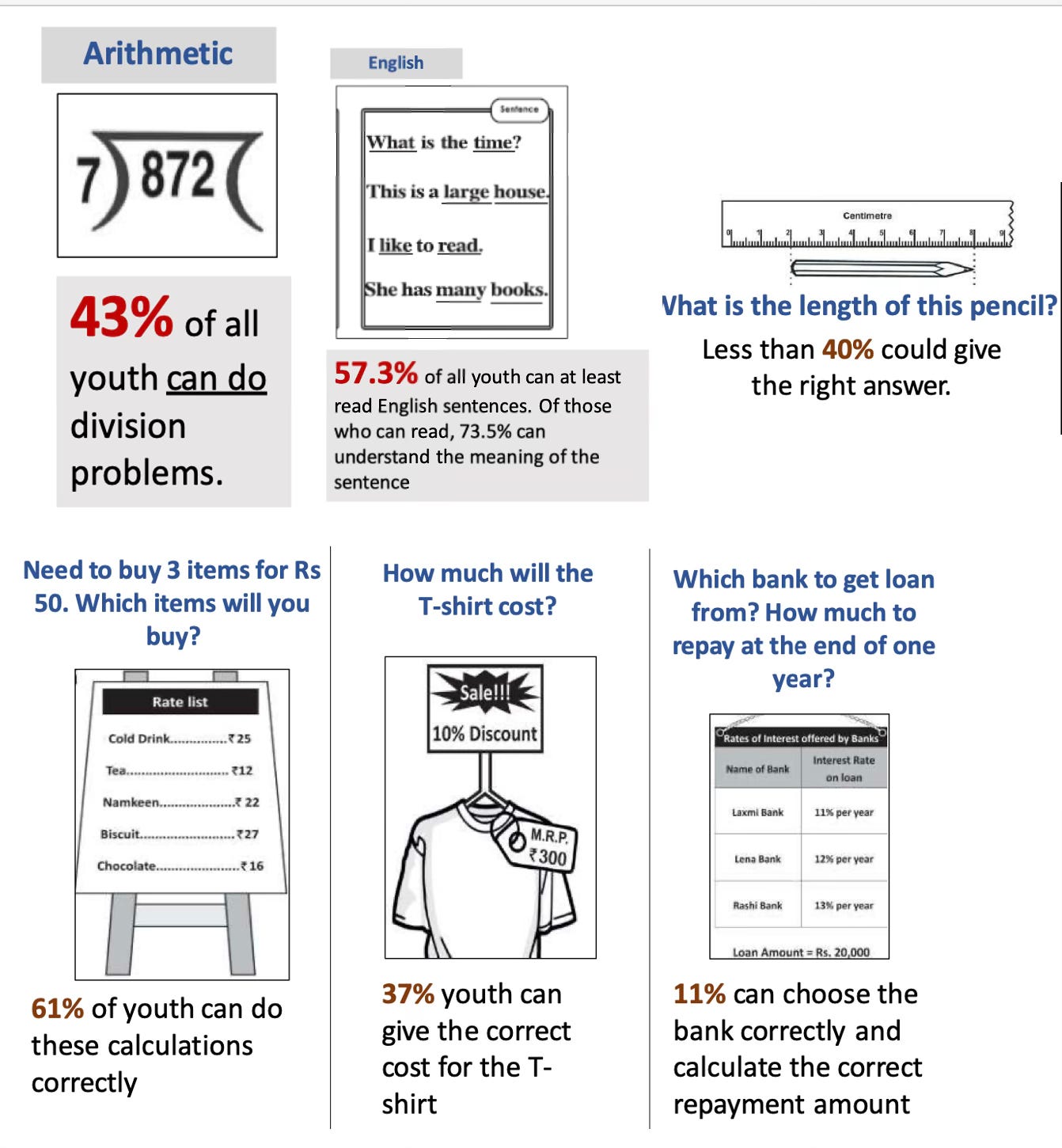

Source: ASER 2023, Graphics

More than half the adolescents couldn’t divide three digits by one digit. 6 in 10 couldn’t use a ruler that did not start at 0. At 14-18 years of age, you would expect an adolescent to have advanced language skills, a somewhat strong working memory, the ability to think abstractly, make judgments, and so on. Complex comprehension and creation of knowledge also develop in this age. However, most surveyed adolescents were struggling with very basic cognitive tasks.

On slightly advanced tasks: a staggering 9 out of 10 adolescents couldn’t calculate repayment amounts and choose the better option given simple interest rates of banks. More than half the adolescents couldn’t tell how many hours a person slept, given the time at which they slept and woke up! 4 in 10 people who knew arithmetic still couldn’t answer this. Though very many knew how to use smartphones, only about 40% of adolescents knew how to use a computer. These tasks require some attention, basic numeracy, logical reasoning, and reasonable executive function, but nevertheless are easy tasks we would presume someone with more than a few years of schooling would be able to perform effectively and easily. Still, too many of our adolescent youth couldn’t. 35% of adolescents surveyed couldn’t follow three out of four instructions on a basic ORS packet explaining how to make an ORS drink.

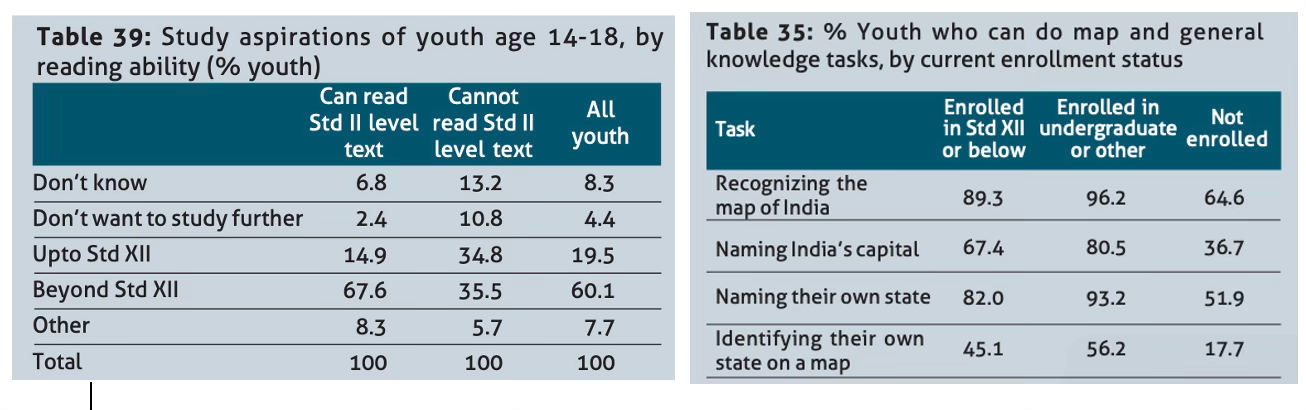

Where is the problem though? Did they forget basic activities? That is unlikely, because, guess what, most of them were still in school! One-third of those enrolled in school, were also working for more than half of the last month! Likely, they never picked these skills. Most did not learn division, basic reading, and life tasks like discounting, simple interest calculations, and counting hours in school. Only 5.5% of those tested were attending any vocational courses. In the 2017 survey, 35% of students who couldn’t read class II level text wanted to study beyond class XII! Further, more than half the adolescents couldn’t tell where their state was on the Indian map.

Source: ASER 2017

What were the aspirations of these young adolescents? The 2023 survey captures this. Most wanted to join uniformed services or write the myriad government exams. [Which in itself has many difficult consequences]. About 36% of adolescent men wanted to join the Armed forces or some other government service. 27% want to be in the Army or Police, often for lack of different role models. Most adolescent females wanted to be teachers, nurses, or doctors or were undecided.

Stare at the chart that follows for a long-ish time. A lot of our social problems are reflected in it. See how many you can identify. This has been explored in some detail in the ASER report which I recommend you read. But let me remind you, that more than half of these can’t divide or read more than a few sentences in English with comprehension.

Source: ASER, 2023

Does this worry you? After 10 years of school? Hold your breath. Let us go a few grades lower. Adolescents aren’t but are our children learning?

Children in India: No learning at all

Almost all our children up to 14 years of age are in schools. 80% of three-year-olds were attending some Anganwadi, pre-school, or school. 88% of four-year-olds were. But wait a second, how many children is that? We have about 26 crore children in schools and roughly 15.6 crore children are studying in schools that are government schools or government-aided (urban and rural).

As per ASER 2021, too, 70% of the children attending schools in rural India are in government schools. COVID also seems to have hastened the move to government schools somewhat. 4 in 10 children were in addition also attending some form of tuition. At age 15 roughly 8-10% of children stopped attending school albeit, with much inter-state variation. E.g. 17% of 15-16-year-old girls in MP were not attending school! The stakes in this are very high.

Now on to their learning;

As of 2022, a shocking 75.5% of class V students across India could not read four five-word English sentences. Pause, hold your breath, and read it again. 3 in 4 class V students couldn’t read class II sentences in English. There was substantial state variation with the number for Kerala touching 30% (Which is still 1 in 3 and a lot) and 92% (!!) of children in Gujarat. Less than 80 of 1000 class V students in rural Gujarat were able to read class II level sentences in English. This is an alarming crisis; of the highest proportion with grave consequences.

Well, maybe they are just bad at English, so what? Here we go:

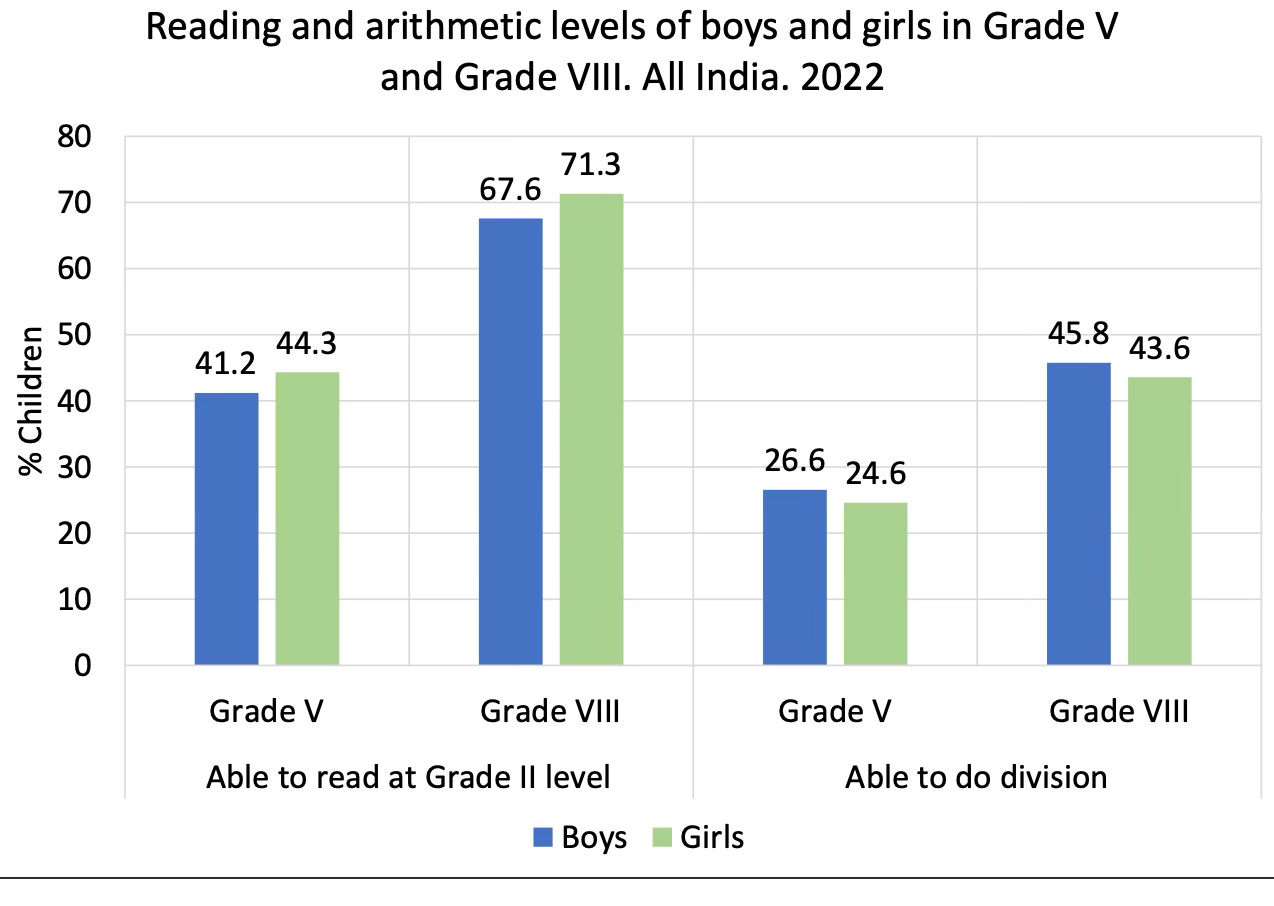

More than half of class 5 students and one in three class 8 students still could not read class 2 text in vernacular languages. Only one-quarter of Class-V students and less than half of an average VIII-grade classroom would be able to perform division. 7 in 10 class III children could not do basic subtraction!! This is a crisis. Of the highest proportion.

Private schools fare somewhat better on some counts, but the reasons are less understood in research. Some even argue they generate equal learning as government schools. Parents certainly preferred private schools, but going by ASER findings that seems to be because private school-goers spoke better English. Private schools certainly gave more learning per-rupee but matters are more complex there since some argue that government schools have disproportionately more first-generation learners to cater to. Summarily, there is a lot of diversity within schools and the socio-economic classes of children they cater to. ASER also shows that the condition of the households and parents’ levels of learning for children they survey have improved over time, but that does not seem to have translated into better aggregate learning outcomes for children.

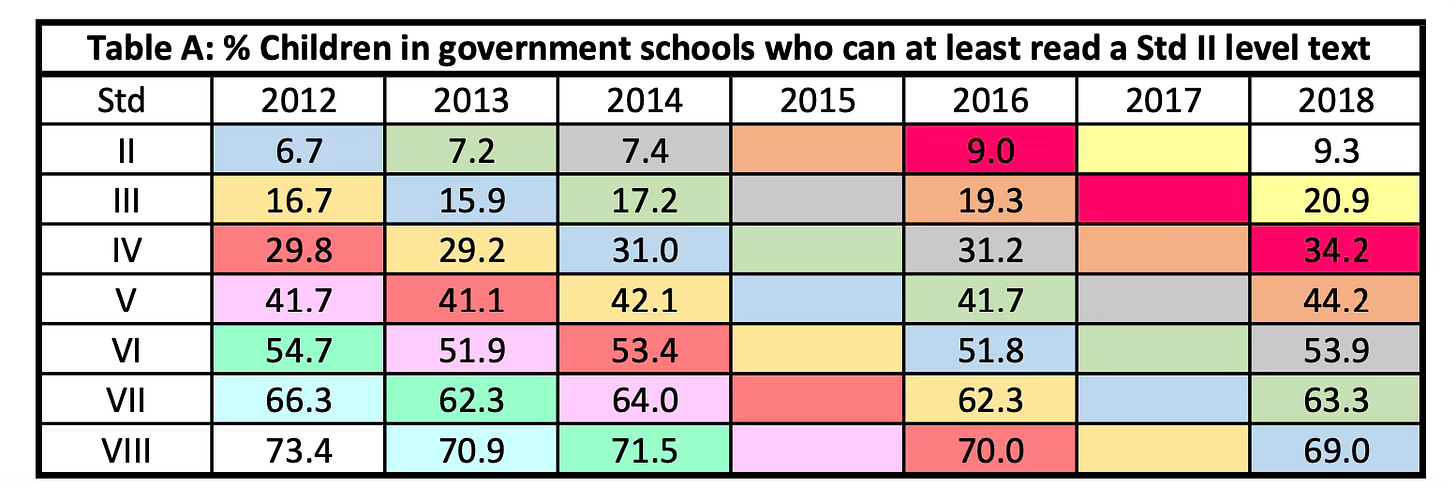

One may argue, well, for all it counts things must have surely improved over the last decade. After all, progress is slow in these matters. Education is complex business?! Let us turn to that. The grade-level improvement in the proportion of children with any specific learning skills has been more or less flat over the last decade. There is no area of Indian life that has not changed over the decade, except learning in school. We are where we were exactly ten years ago. In some ways worse.

Source: ASER Learning Trends.

But hey, we have given everything to schools! After all, the spending has increased so much. Not so many computers and books certainly, but a lot of basic infrastructure? Then what are we missing? Something seems wrong, doesn’t it?

Caveats and Context

Is it only an outcomes and process/implementation problem and we have solved for inputs? Before we come to that let us learn some more important contextual caveats:

First— Single-teacher schools and multi-grade classrooms: As many as 1,17,285 or 7.9% of total schools were single-teacher schools. We have too many districts where more than 10% and in some even 20% of the total schools are single-teacher schools. About five districts had over 1000 single-teacher schools, some like Barmer because of the terrain. Few schools also have issues with access-roads, particularly in Northern and North-eastern hilly areas. These need to be solved urgently. Single-teacher schools mean multi-grade classrooms and that is bad news for learning. Only 6 in 10 schools reported that their classroom spaces were in good shape, some effort towards fixing that must also be eyed where costs are permissive. This does zilch to improve learning but makes for a warm and inviting learning space.

Second— School size, composite schools and rationalisation: The average size of a rural government school is 150 students. The number falls to 115 for primary schools. Going by the PTR, in an average school there should be four classes of roughly 30 each and about three-four teachers. But that is for the average. Average is the most misleading of all statistics. Just like for learning levels, the distribution of PTRs can also be skewed, especially if discretionary deployment of teachers in required locations is a challenge or ensuring attendance in some areas for example is an issue. Composite schools which are merely 9% of total schools housing more than one school section (primary/secondary) in the same compound have 27% of the teachers and students with an average size of 518 students. Senior Secondary schools have an average size of 267 students. More composite schools and more teachers would certainly help because they create a better cohesive environment for the teachers. The NEP is trying to have us move in that direction, except the provisions about this in the original draft have been narrowed to give states more flexibility on this aspect. There are also problems relating to the deployment of female teachers and transfers to some blocks of specific backward districts or in single-teacher schools that make matters worse. States albeit have been trying to rationalize transfers, posting locally wherever possible so as to make PTRs homogenous across schools. See these national rationalization guidelines too for instance.

Third—School level PTR and RTE: The PTR in government schools for primary and higher secondary students overall is 27:1 and is much lesser for intervening standards. Albeit, at the school level, the PTR may often be worse. One in four schools teaching class VI-VIII have a PTR exceeding 1:35. 70% of schools in Bihar exceed the 1:35 ratio. The evidence on how effective reducing PTR is, is split. For all the problems in transfers “for PTR maintenance” that it creates, the RTE act mandate u/s 25 must be amended. It ought to be a guiding principle. RTE itself may be recast in the mould of the NEP. (See Sections 21-22 which have failed miserably and onerous curriculum requirements for teachers in Section 24.) Having more teachers can also help effectively tackle the multi-grade classroom problem. But PTR by itself is not a useful metric for determining quality of education but where it leads to multi-grade classrooms or single-teacher schools, it becomes critical.

Fourth— Let us do away with the myth that country-wide we have too many teacher vacancies. According to an official source, we have staggering vacancies of teacher posts [Statewise] in government schools. In UP alone, 39% of teacher positions are vacant. In Karnataka 57% of teacher posts are vacant. The total number of vacant teacher posts across India according to this source is 12,54,773! That is approximately one less teacher per about 110 enrolled students. The numbers seem overstated and calculated based on applying the threshold PTR as prescribed in the RTE to every school. Except in some states, teacher shortage is not a problem and aggregate PTRs are optimum.

Fifth— Most states have under 1:30 pupil-teacher ratios as recommended by the NEP and the RTE Act. Some states like Bihar, Jharkhand and UP have higher pupil-teacher ratios. E.g. Bihar government schools have a pupil-teacher ratio of 57:1. These states could certainly do better with teacher hiring and efforts are being made to that effect. Hiring and transferring teachers requires substantial political capital because teachers are embedded in state politics. Teacher Unions (also see, and this) are also powerful and influential.

Sixth— Contract teaching: We have as many females in teaching as males, perhaps even a little more than males. Teacher absenteeism without reason is between 2-4% and reasonable for public officials. While, often the other duty burdens on teachers may be high leading to less presence in school. Training, poll management, census, vaccination, COVID response, cattle census, ration card verification are sample tasks that teachers are routinely expected to do. 11% of hiring (about 5.5 lakh teachers) in government schools is contractual, almost entirely in rural schools. Except in states like Jharkhand, most teachers have some teaching qualifications. Jharkhand also hires more contract teachers. Only about 10% of teachers in India have no professional teaching qualification. Notably, 60% of these are working in private schools. But whether degree, gender, teaching qualifications are related to learning levels at all is inconclusive. The education community is split between two camps. One, which recognises the importance of securing teaching as a career and teacher professionalism. Second, which would argue that contract-teaching or hiring teaching assistants with lesser qualifications is cost-effective and can with some training, given their intrinsic motivation be effective at delivering basic learning skills. The third camp where I sit argues that both can co-exist. But, the UP para-teachers’ assimilation as assistant teachers to cater to their career concerns and to respond to political manoeuvring by para-teachers was struck down by the SC because the Shiksha Mitras as they are called had not qualified TET and were underqualified. The court order led to the cancellation of about 1.78 lakh appointments. This has meant that experimentation with teacher hiring will go on a lull in India for a while to come. But like I said, and to reiterate: We have near about enough teachers!

Seventh-Courts: Courts have also been difficult to circumvent in schooling, teacher hiring and related policy efforts. Stays on appointments for scams in teacher hiring Bengal, and tussle on hiring teachers in UP (Also see) which has been ongoing for five years now are instances where the court had to stay or even cancel appointments of thousands of teachers. Sometimes the courts have simply overstepped. For example, in an ironic judgment, they held B.Ed is not a valid qualification for primary school teachers in Chattisgarh, only a D.Ed. is [B.Ed. is a higher qualification]. In Odisha, it took three years for the High Court to overturn its decision disallowing rationalization of schools. New Transfer policy in UP too got overturned [https://l1nq.com/1uuuc] by the Allahbad High Court. Sometimes, courts have added to the confusion. Allahabad, Bombay, and Karnataka High Courts have given conflicting judgments on an important aspect of the parents’ right to choose private even when public schools exist under the RTE Act. This matter remains pending in the Supreme Court. Paper leaks (See Bihar, Rajasthan make matters worse for hiring. With some seriousness, none of these challenges are insurmountable where hiring is necessary at all. But I contend that most states don’t even need hiring they just need better, professional, and politically insulated HR management.

Eighth—Area-specific issues and teacher quality: While the things we said in one to four are true on average, we must be mindful of aspirational districts and state-specific (Parts of Jharkhand, Bihar for example) issues and areas where a lot still needs to be done. Teacher quality and teacher education(1) is sometimes compromised but I believe it is beyond the scope of this article to assess that carefully; so it suffices only to acknowledge that fact.

What does all of this mean?

What is the point of all of this, you may ask? It’s this: We have functional schools with much of the required amenities, we have sufficiently staffed schools except for the challenges highlighted above, and yet most of our school-goers and adolescents can’t read, can’t do basic arithmetic, can’t execute simple cognitive tasks. Without a surprise that 40%+ of our graduate workforce is unemployed. We did not school them, they are struggling! They are struggling with the math, the reading and they are struggling with self-esteem. We also can see that courts and politics of school policies can be difficult to navigate, especially with powerful teacher unions

Can we not spend more to solve these problems? According to some sources, 80% of our school spending is on teacher salaries and teacher training. Our total spending on education is a little over 4% of GDP and roughly 15% of the total government expenditure which is in keeping with global norms. We spend about 5.95-6.25 [2020-21 figures, so take with a pinch of salt] lakh crore rupees Union, State, and UT governments put together on the revenue budget of elementary and secondary education. Elementary education is half state and half union expenditure and secondary education is almost entirely state government spending. We are roughly, back-of-the-envelope, spending 38-40k rupees per child (revenue account only) on government school rolls every year. But we have achieved no learning at all. Some analysts have gone as far as to argue that the government should just give out the per pupil money as cash. Unfortunately and most importantly:

Only 25% of our elementary education revenue budget and 12% secondary education revenue budgets are being spent by local bodies!

India does not participate in any international school-student achievement rankings like the PISA. The reports had to be buried, the one time it did as India stood second from the bottom. We also understand things like when villages get access roads—enrolment increases are conditional on the opportunity cost of attending school, our children learn better arithmetic in bazaars and are fluent at those transactions but struggle in schools. Test scores have to be made up to cater to the endless kaagzi-kaam and aankdebaazi required of the teachers and administrative data collected through testing by schools is non-sense.

Why is learning so important?

Almost the entirety of social transformation and the edifice of development hangs on getting schooling and basic learning right. Without fixing this, we are chasing a chimera. Our social issues—caste for example, a new politically-active citizenry that reads, discusses, and debates and is not afraid of rules, our promise of economic development, the transmission of new-age values, training self-learners, nurturing sense of entrepreneurship, cultural ideas, aesthetics. [Note from the aspirations part of this blog how no child wants to or can afford to be an artist, what an ordeal for a civilization!] The continuance of the Indian dream, if there ever was one, hangs on teaching our children to read and subtract. It has never been more urgent than now.

Finally, the most important question that Ajay Shah once asked must be asked of our schools: are we doing enough on all five of the Big Five Personality traits? Or are we endlessly focusing on conscientiousness? Can we ever move away from heaping praises on conformism, rote-learning, and from endlessly testing and sorting children?

While we move to exploring the more systematic issues with Akshay, we must acknowledge that within the government there is an increasing seriousness and initiative to tackle the deficit in functional literacy and numeracy. NIPUN Bharat, Ankur-MP, NIPUN-Axom, etc. have been initiated to plug this essential gap in literacy and numeracy. But the structural issues persist.

Let us now engage with what Akshay writes about those.

The devil is in the deviation from the rule

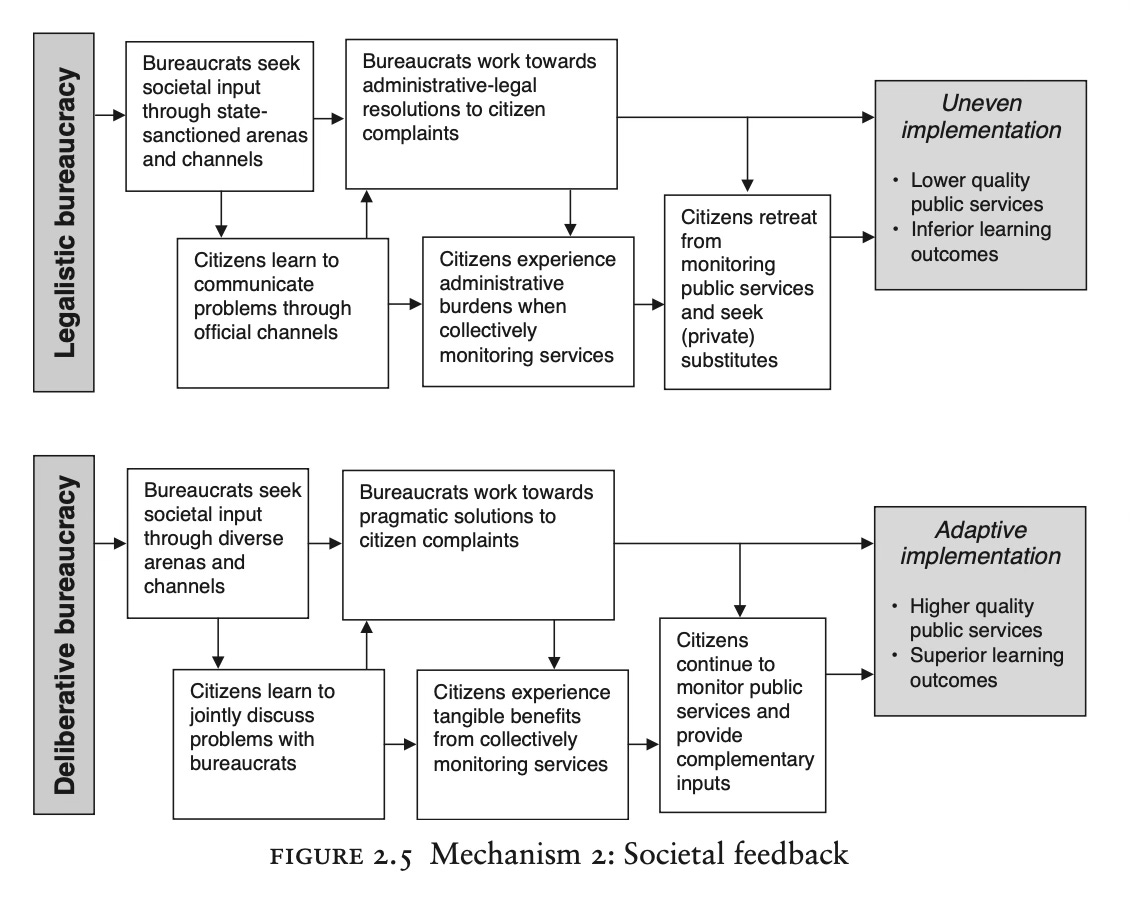

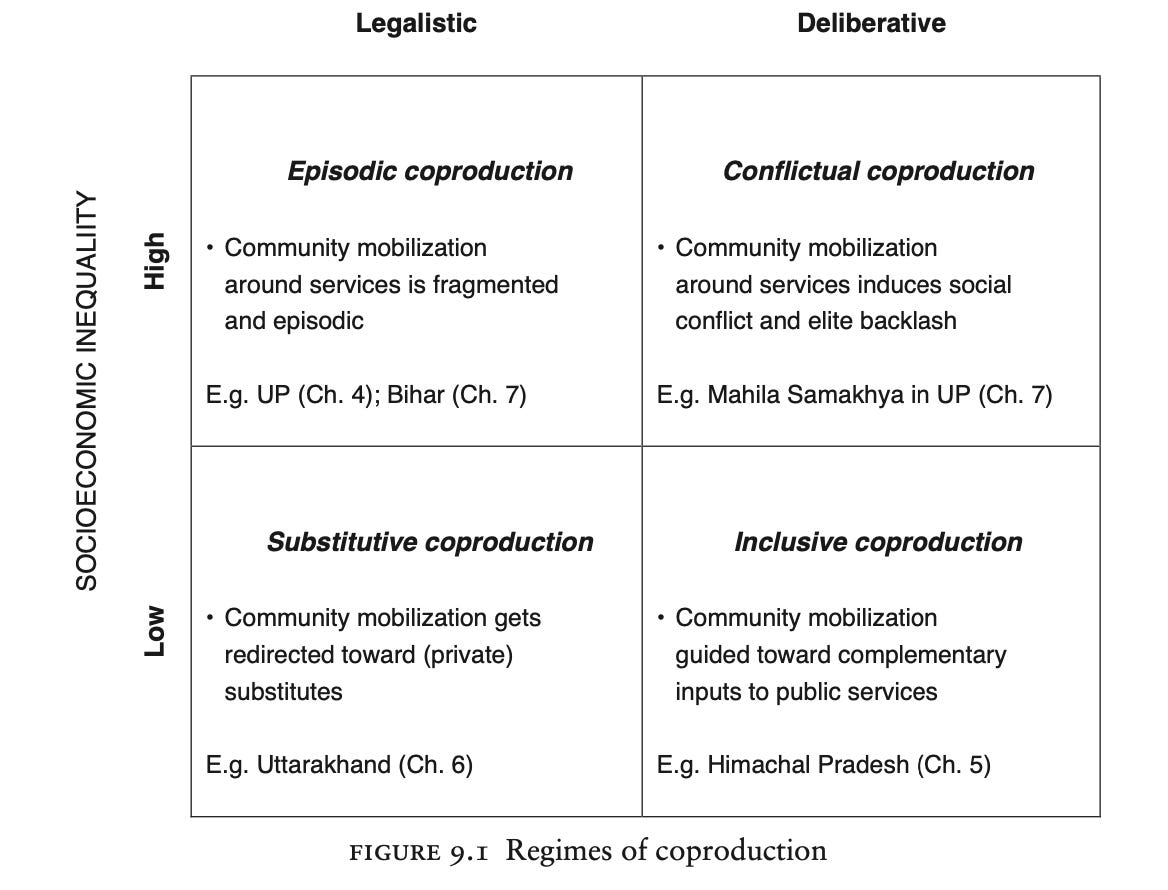

Akshay in his article argues that failure in delivering primary education is primarily an implementation problem with solutions that may be political. He argues further that the capacity of Indian governments is limited, good at episodic bedazzling delivery but much less effective in ongoing service delivery, and has stretched local capacity following Devesh Kapur. It is further limited by legalistic bureaucracies.

What does legalism mean though?

“Legalism is the ethical attitude that holds moral conduct to be a matter of rule following, and moral relationships to consist of duties and rights determined by rules.” ..[and rules only]

Akshay then argues that education is a complex and politically embedded social process, much like Anurag Behar, requiring substantial input from non-actors like parents. Education in other words is co-produced. Learning happens outside schools too, but non-actors’ engagement with schools must be facilitated for any meaningful learning. Who are these non-actors though? What do they want? Parents who want the best learning for their children, and the village-community that should want accountability of teachers are two prime examples. Anurag would suggest that a ‘social human process’ means we need to trust the teacher and let her figure out how to hold attention and teach her students while the rest of us keep a thick check on the functioning of the school and support the teacher and the child. Anurag also cautions us that what appears like an education-only problem might in fact be a deep-soil state-capacity and state-mechanisms problem.

Akshay gives us a vocabulary to understand this deep-soil through his careful study of the three different levels of government. I endorse his idea that one of the crucial elements of success in delivering education is that:

The local bureaucracy must operate deliberatively-emphasizing adaptivity and flexibility rather than legalistically- emphasizing rule-compliance, for both formal and informal bureaucratic rules.

The Ideal Shiksha Vibhaag Karmachari

For effective co-production of learning, in other words, it is important that the median local shiksha vibhaag karmachari be motivated, purposive, flexible, patient listener, reasonable, responsive and collaborative in addition to (perhaps instead of) things mandated by his Weberian service rules [Sample]. He further asks that the bureaucrat must sometimes also be activist-y where conflict or inequality are barriers to participation! Legalism is fatal to complexity. Legalism seeks to conserve existing norms and power structures. This reminds me of an incident, narrated by Karthik, where a local bureaucrat once asked Rukmini while she was exposing fake data and aankdebazi to the villagers: “Aapko sachchai se itna lagaav kyu hai?” Rule following is in itself a self-sufficient virtue in legalistic bureaucratic systems, even more so that being truthful.

Source: Akshay Mangla, Making Bureaucracy Work

His contention is that rule compliance can make the delivery of complex services hard, the bureaucrat must instead be problem-oriented. He must engage, deliberate, act, and course correct— focus on the process too. There is a permanent trade-off between administrative control and deliberative discretion. That is manifest in rule compliance and deliberation. Most officials operate on the golden mean, excluding the ones who are less efficient or corrupt. Being a government officer is a riveting balancing act between rules, sensibility, compassion, law and stakeholder opinion. Akshay suggests, that more flexibility in adaptation would be a great favor to the local bureaucrats who are checked and tied too stringently by their own legalistic culture.

Source: Akshay Mangla, Making Bureaucracy Work

Paper trail and compliance culture

How do rules change anything though? Aren’t rules a good thing? Firstly, Rules necessarily mean checks, and checks often mean paper trails. NCTE here lists the 75(!) types of records and registers schools may want to keep. Government teachers are required to keep a lot of these. I have filled many of my mother’s forms and sheets who was a government school teacher. Further, every rule requires compliance. Rules reduce principle-based discussions and restrict the scope for tailored innovation or course correction. Rules over-prescribe the right ways to connect input to outcomes—only if we had a size that fit all. More rules mean teachers are bound by diktats and are at the whims of entities external to the challenges of that school— yes, each school is a unit by itself—like Anurag argues. Stringent rules mean teaching and the teacher is reduced to targets and sheet-forms. The social recognition that the teacher seeks to claim for herself is limited to the reams of reports she must send back to the AO. Akshay further identifies two important limbs on which the failure to deliver services lies:

The inability of the local bureaucracy to deliberate and the insulation of local state from the top-heavy planner state.

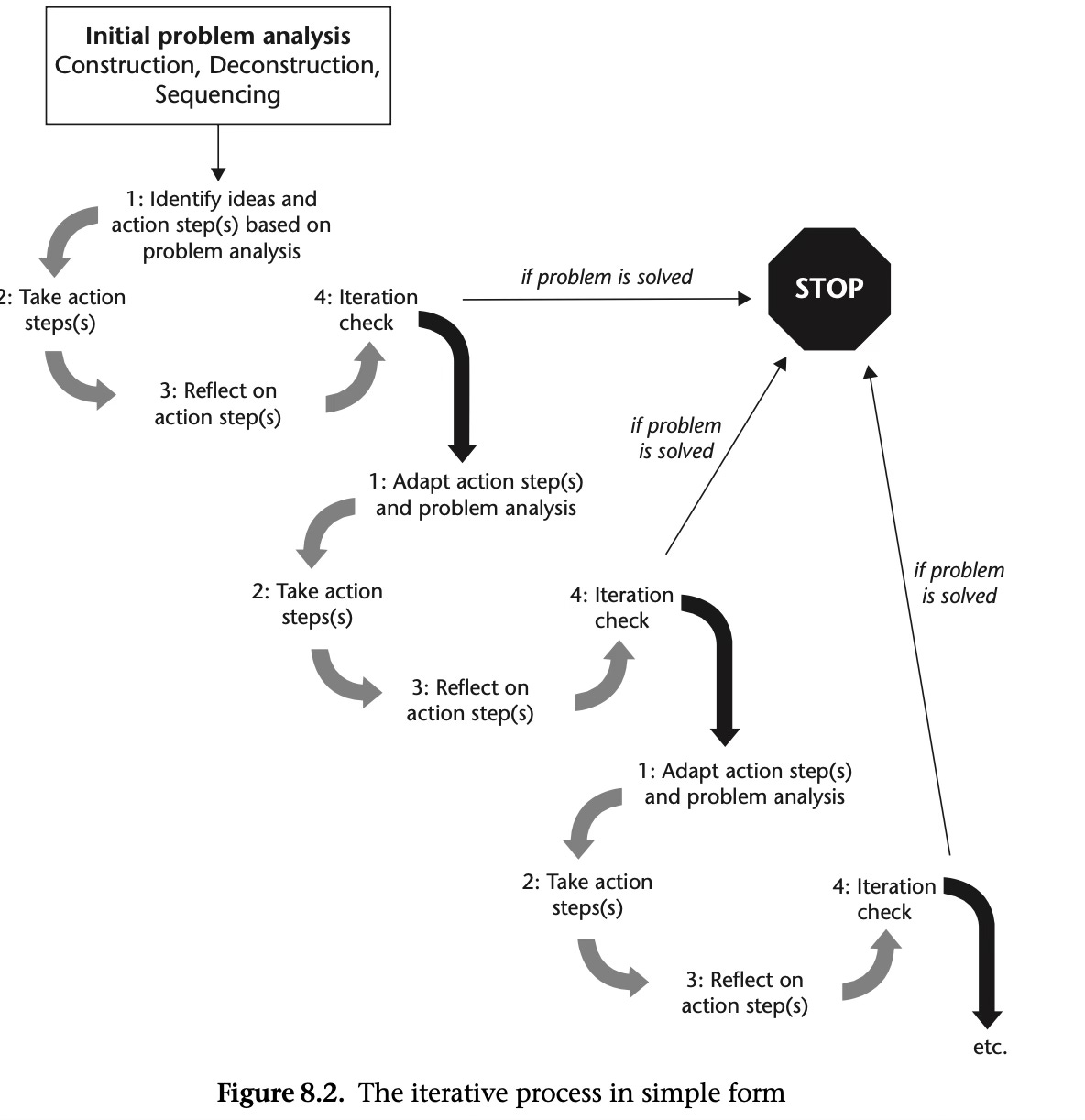

This sounds much like a culture problem! Norms develop to favor conscientiousness at the cost of iterative deliberation. This is not new to us. Lant has been arguing a version of this for a long time now. Here is his framework for iteration for example from his book which is a bible [Thanks to Chris Blatmann for introducing this book] for students of bureaucracies:

Source: Pritchett, Woolcock and Andrews. Building State Capability

He is not alone. Ashish, in his excellent article, points out that we should create multiple local Coasean equilibria, and stop searching for one grand equilibrium bargain grounded in precisely specified rules. Karthik calls it decentralized experimentation. Biju calls it participatory development. They are all referring to less centralized control, more deliberation, more adaptation, and tailoring. The school can’t operate like a franchise following precise rules, it needs to be its own firm with the teachers in-charge. These many economists rarely have a consensus on something; anytime that happens we must grab the opportunity.

If you don’t take anything else from this blog post, do take along this metaphor by Pritchett where he summarizes it with a precise metaphor:

“In many countries, the legacy system of schooling is a large government-owned spider.”

“[We] ..adopt the metaphor of a spider because a spider uses its web to expand its reach, but all information created by the vibrations of the web must be processed, decisions made, and actions taken by one spider brain at the center of the web.

The starfish, in contrast, is a very different kind of organism. Many species of starfish actually have no brain. The starfish is a radically decentralized organism with only a loosely connected nervous system. The starfish moves not because the brain processes information and decides to move but because the local actions of its loosely connected parts add up to movement.”

Lant Pritchett, The Rebirth of Education: Schooling Ain't Learning

Accountability Crisis?

But how do we layer that much flexibility with accountability, transparency, and uniformity? How do we achieve these three benefits of a strictly Weberian Bureaucracy when discarding it?

Turgid rule compliance, Akshay argues, dissuades participation because people are unable to keep up with the maze of rules. In an idea that might sound counter-intuitive, he suggests that less legalism makes accountability thicker! It allows non-actors to participate and enhances ways in which actors can engage with these non-actors. Akshay also suggests as one of the ideas that political parties could operate at a level of administrative mechanisms influencing planning and use of public resources rather than just spending. But this also exposes the local bureaucracy to manipulation and control by local actors, especially in places where there is insufficient local competition for power, or where local governments are choked, like in Maharashtra. What is the consequence of this tradeoff? I must admit I do not know. This is a top-right corner challenge on an importance-difficulty matrix of the Indian state’s challenges.

Akshay also highlights that community mobilization for accountability may not always be viable. See this excellent chart for example:

States like Kerala that have excellent Panchayati institutions have less to worry. However, most states do not have local participation as an embedded social value. How do we nurture it against all the myriad local interests eager to capture the state? Can it be nurtured at all? Over the short run, unlikely. How else do we demand accountability? Again, I do not know.

Akshay then leaves us with some gaps. How do we sustain this engagement of non-actors? How do conflicted societies resolve the challenge of doing new things? How do we go from small-scale knowledge to large-scale effectiveness while keeping a mere rule-compliance minimum [The RCT version of this is here ]? Biju Rao has hinted at some answers: when ‘cultural configurations, spirit of improvisation or values replace rules.

Acemoglu shares this important idea as a theoretical consideration that over-incentivization in bureaucracies can lead to wasteful signaling. We have both problems of under-visibility and under-incentivization for teachers and low-ranking bureaucrats and over-visibility and over-incentivization of higher bureaucracy and politicians in India. This leads to a state that is split from the center into two halves with different priorities. We also have a socio-economic structure that is split into clear silos and these two splits of bureaucracy and the society often amplify each other through Hirschmannian dynamics of Exit, Voice and Loyalty. This problem of the state which is manifest in every development challenge has become the glass ceiling of public education in India. It in my opinion is the most important phenomenon leading to inputized education.

Probable starting points for solving the problems

There are in my opinion three important things needed to urgently tackle this, most of which have also been prescribed by Karthik in his new book. NEP also considers some of these closely.

First, shift the goalpost and fix it there; As Karthik also suggests, make third-party aggregate and objectively measured learning outcomes data at some ward/block level the most valid criteria for signaling, leave everything else to the ward/block officer— I must caution that it is a difficult thing that is being asked—we are asking to shift values.

Second, which in my opinion is more practical, deregulate schooling, and decentralize funding to Zilla Parishads and local bodies and be light and skeletal in prescription. Flatten the local bureaucracy, assert the importance of the teacher, and assert minimum accountability but implement it strictly. E.g. The teacher showing up in school must be non-negotiable, all his students passing the grade-level math exam need not be.

In admin lingo: Zamini Sthiti must not be distorted, but it need not be rigidly niyam-baddh. Prashaasan Karyapaddhati needs to be flexible allowing adaptation and must be shikshak-kendrit. Prashaasan must be less anxious about being dheela, and use the danda sparingly.

Third, cut the paper trail, free teacher time for teaching, change the nature and scope of accountability and substitute it with support wherever possible, and bestow cultural value and dignity back on the profession. Take Anurag seriously when he says “Teachers are our only hope”.

In admin lingo: Dhaandli and ghapla in musters need to be prevented. AO must do visits for niyamit nirikshan, but she should not do too much dakhalandazi in the teacher’s role. She must support the teacher wherever possible. Kaagzi kaam must be rendered unimportant and not a part of teachers’ duties. A teacher’s pehchaan in the vibhaag must be by her students’ abilities and the environment in the school and her classroom and not by kaagzi kaam. Teaching must not be anya kaam and everything else should be made to wait where it can wait. The teacher should have no other duty, she should only ensure children learn.

The second suggestion, I believe would mean insulating school education from both the existing executive and the judiciary into an independent branch with clearer and limited mandates. The first and the third need a lot of socio-political engagement. In all three we lack capacity and expertise across all levels of government. Just the idea rings so foreign to us! But we need to build capacity. Capacity can only follow with responsibility. We need to do all three, do it now and do it fast. Is this premature load-bearing? That needs more research. But, tentatively for the amount of futility this will reduce it will free up a lot of time and money. It’s a reorientation of purpose, not excess load-bearing.

Karthik has laid out a blueprint for us to debate remaking the Indian developmental state. We will have to skip the details, be skeletal, and adopt the starfish approach. Because rules govern the process of their own becoming. Operation and practice of the rules is in reference to the ideal it embodies and seek to uphold. We must emphasize the ideal and impress it. Prescribe too much content and we are in trouble again. Is this impossible? Maybe not, but it is certainly very very difficult. Delhi did all of it, somewhat successfully too; and we have no other choice. The stakes are too high!

Schooling is a unique challenge

School Education is unique. Everyone agrees it is important. There is a broad agreement on what kind of solutions are workable. We are spending money on both inputs and teachers. But, we haven’t really gotten anywhere. We have a somewhat successful diagnosis of what might be happening: sorting, teaching to the test, teacher incompetence, unreasonable expectations from the system, poor quality teacher training, multi-grade classrooms, mother tongue-local language dissonance, poor early child education, a large burden to undo the loss on the lottery of birth, burden to invert rigid social structures, failure to make children loved and welcome in school, inability in catering to teacher dignity and career aspirations. The verdict is more split on effectiveness of contract teachers and relevance of teacher qualification, more or less top-down structure prescribed in curriculum and teaching-style as per experience and skills of the teacher, more infrastructure or less, no detention policy, etc. But all of this put together, what is certain is that the status quo has led to the worst outcome possible, and probably the most dangerous: ten years of schoolin and allied efforts and most of our children and adolescents can’t read, subtract or divide!

Weberian bureaucracy is a very poor choice for running many lakh schools. It is a also a bad choice for running a few hundred schools. It may be a good choice for running about 10 schools but only if the head of the chain is a thinking bureaucrat, if he is the spider. Teaching can be structured, but it cannot and may not be mechanized. Whatever changes we make will always be better on average than what we have right now. What we have right now is a massive crisis. Mere paens to accountability and a quest for a hyper-responsive system is a lame excuse for the existence of rules that go straight to the heart of the purpose of the institution. How do we make a gradual transition from a spider to starfish is something we should all think about. Education is freedom, an institution that can’t breathe freedom; will never transmit freedom.

If you read or skimmed the article till here, I am grateful. This article is a work in progress and I will keep updating it. If you are interested in learning more about the issue, please consider reviewing the links attached throughout the article and at the end of the article. Your feedback and disagreement is very valuable to me. Thanks to Akshay Mangla for his blog which motivated me to reflect.

Additional Reading:

Highly Recommended—Anurag Behar, A Matter of the Heart

Akhil Gupta, Red Tape

Recommended— Subir Shukla on unpacking the complexity of Teacher Professional Development and how it needs to be transformative. How do we do it differently ? What are some of the challenges? [https://youtu.be/Okw1opKfKYU]

Subir Shukla on how education systems learn. [https://youtu.be/NqJorDjPnGQ?feature=shared]

Manish Sisodia, Shiksha

Lant Pritchett, The Rebirth of Education, Schooling ain’t learning

The GEEAP report on interventions for cost-effective learning

TISS report on teachers in India using UDISE 2021-22.

Teacher absenteeism in India, Azim Premji Foundation

Ashish Dhawan on FLN, Convergence foundation

Karthik Muralidharan on Education and the Indian State on the Seen and the Unseen. 1, 2, 3. Karthik’s paper on reforming Indian education

Pritchett’s latest framework for analyzing school education and learning

A brief primer on powerful teacher unions in India.

For the Marathi listeners - The Genius of Vyankatesh Madgulkar narrates an AO’s inspection, PL’s Chitale Master, Bigari te Matric

Some collected cultural references to schooling.

Well referenced article. It raises some questions in my mind. If ASER runs similar study in other parts of the world, how would they compare with us? Any available international study?

Secondly, If we run this survey across reasonably successful adults in different fields, would there be a correlation in their performance vs success rate?

AAP government tried reforms in education in Delhi, was there a marked improvement?

Very informative and thought provoking!! Great read! 🙌